Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Endocrinol Metab > Volume 36(5); 2021 > Article

-

Review ArticleThyroid T4+T3 Combination Therapy: An Unsolved Problem of Increasing Magnitude and Complexity

- Wilmar M. Wiersinga

-

Endocrinology and Metabolism 2021;36(5):938-951.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2021.501

Published online: September 30, 2021

Department of Endocrinology, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

- Corresponding author: Wilmar M. Wiersinga. Department of Endocrinology, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, the Netherlands, E-mail: w.m.wiersinga@amsterdamumc.nl

Copyright © 2021 Korean Endocrine Society

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- ABSTRACT

- INTRODUCTION

- T4+T3 COMBINATION THERAPY: A QUANTITATIVE APPROACH

- PREVALENCE AND NATURE OF PERSISTENT SYMPTOMS DESPITE A NORMAL TSH ON LT4

- PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS FOR PERSISTENT SYMPTOMS ON LT4

- HOW TO MAKE PROGRESS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PERSISTENT SYMPTOMS ON LT4 DESPITE A NORMAL TSH?

- Article information

- References

ABSTRACT

- Thyroxine (T4)+triiodothyronine (T3) combination therapy can be considered in case of persistent symptoms despite normal serum thyroid stimulating hormone in levothyroxine (LT4)-treated hypothyroid patients. Combination therapy has gained popularity in the last two decades, especially in countries with a relatively high gross domestic product. The prevalence of persistent symptoms has also increased; most frequent are complaints about energy levels and fatigue (80% to 90%), weight management (70% to 75%), memory (60% to 80%), and mood (40% to 50%). Pathophysiological explanations for persistent problems are unrealistic patient expectations, comorbidities, somatic symptoms, related disorders (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-5]), autoimmune neuroinflammation, and low tissue T3. There is fair circumstantial evidence for the latter cause (tissue and specifically brain T3 content is normalized by T4+T3, not by T4 alone), but the other causes are viewed as more relevant in current practice. This might be related to the ‘hype’ that has emerged surrounding T4+T3 therapy. Although more and better-designed trials are needed to validate the efficacy of T4+T3 combination, the management of persistent symptoms should also be directed towards alternative causes. Improving the doctor-patient relationship and including more and better information is crucial. For example, dissatisfaction with the outcomes of T4 treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism can be anticipated as recent trials have demonstrated that LT4 is hardly effective in improving symptoms associated with subclinical hypothyroidism.

- In 1996, 25 years ago, Escobar-Morreale et al. [1,2] reported that only combined treatment with thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) restored euthyroidism (as judged by normal T4 and T3 tissue contents) simultaneously in all tissues of thyroidectomized rats. In 2006, 15 years ago, a meta-analysis of 11 randomized clinical trials performed between 1999 and 2005 was done, comparing T4+T3 combination therapy and T4 monotherapy; it did not find any difference in the outcomes of both treatment modalities, either in effectiveness or in safety [3]. Furthermore, in 2012, 10 years ago, the European Thyroid Association (ETA) published the first guideline on T4+T3 combination therapy [4].

- In the absence of evidence showing superiority of T4+T3 combination therapy, interest in the combination nevertheless continued to grow, specifically because it might potentially resolve persistent symptoms that do occur in 5% to 15% of hypothyroid patients despite treatment with levothyroxine (LT4) and reaching a normal thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level [5,6]. T4+T3 therapy became rather popular. The 2012 ETA guidelines were specifically offered to enhance safety and to counter indiscriminate use of T4+T3 combination therapy, which “might be considered as an experimental approach in compliant LT4-treated hypothyroid patients who have persistent complaints despite serum TSH values within the reference range, provided they have previously given support to deal with the chronic nature of their disease and associated autoimmune diseases have been ruled out” [4].

- What progress has been made in the last decade? Obviously little, as the proportion of dissatisfied patients has increased as well as the number of prescriptions of T4+T3 combination therapy. It remains incompletely understood why a subset of hypothyroid patients on T4 monotherapy has persistent complaints [7]. In this review we will discuss the prevalence of hypothyroidism and its treatment with T4 or T4+T3, as well as the nature and pathophysiology of persistent symptoms on T4 despite a normal TSH. We also propose how to deal with persistent symptoms, including T4+T3 combination therapy. We limit ourselves largely to the literature of the last 5 years, as earlier papers have already been reviewed extensively [8,9].

INTRODUCTION

- Prevalence of overt and subclinical hypothyroidism

- Hypothyroidism is a common disease, occurring 5 to 10 times more frequently in women than in men. The global prevalence of overt hypothyroidism in the general population ranges between 0.2% and 5.3% in Europe and 0.3% and 3.7% in the USA (Table 1) [10]. The prevalence figures from the USA originate from population-based surveys and a statewide health fair [11,12]. The European figures are derived from two meta-analyses of published population studies [13,14] and a national survey in Spain [15]. The Japanese data were obtained at a general health check-up [16], and the Korean data come from the sixth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [17,18].

- Prevalence of treated hypothyroidism

- Is there any evidence for increasing prevalence over the last decades? Epidemiological studies in this respect are limited. Most are based on data obtained from drug prescription and hospital discharge databases. The Thyroid Epidemiology Audit and Research Study (TEARS) study from Scotland reported an increase of 63% in the prevalence of treated hypothyroidism in the period 1994–2001 from 3.1% to 5.1% for women and from 0.5% to 0.9% for men; the year-on-year increase was 7.5% [19]. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys in the USA have described an increase in the use of LT4 from 5.1% in the period 1999–2000 to 6.4% in the period 2011–2012 (P= 0.007 for trend) [20]. The prevalence of treated hypothyroidism in the Italian region of Piedmont was 3.11% (0.23% for iatrogenic hypothyroidism) in 2012, and in Spain it was 4.2% in 2009 to 2010 [15,21]. In the UK, the prevalence of treated hypothyroidism, based on LT4 prescriptions in a national-level database covering 99% of general practitioner (GP) practices, increased by 57% from 2.3% (1.43 million) in 2005 to 3.5% (2.24 million) in 2014; the year-on-year increase was significant (P= 0.03) [22]. Growth in population size or prolonged lifespan in the period under investigation only partially explained the observed increase. In multivariate analysis, the prevalence of treated hypothyroidism was positively associated with female sex, white ethnicity and obesity, and negatively with smoking. It was forecasted the prevalence of treated hypothyroidism in 2025 would increase to 4.65% (3.23 million persons) [22]. These data are in accordance with a prevalence of 3.6% for treated hypothyroidism in north-east England in 2016 [23]. A similar trend was observed in the USA, where the proportion of the population reporting thyroid hormone use increased from 4.1% in 1997 to 8.0% in 2016 (P<0.01) [24]. This increase occurred predominantly in individuals over age 65. LT4 became the most prescribed drug in the USA in 2014 and was the second most dispensed drug in the UK in 2020 [25,26]. A community-based study in the UK found that the median TSH level at initiation of LT4 therapy fell from 8.7 to 7.9 mU/L between 2001 and 2009 [27]. A Danish study in a primary care population demonstrated a considerable fall in the median serum TSH at LT4 initiation from 10 mU/L in 2001 to 6.8 mU/L in 2015 [28].

- Prevalence of T4+T3 combination therapy

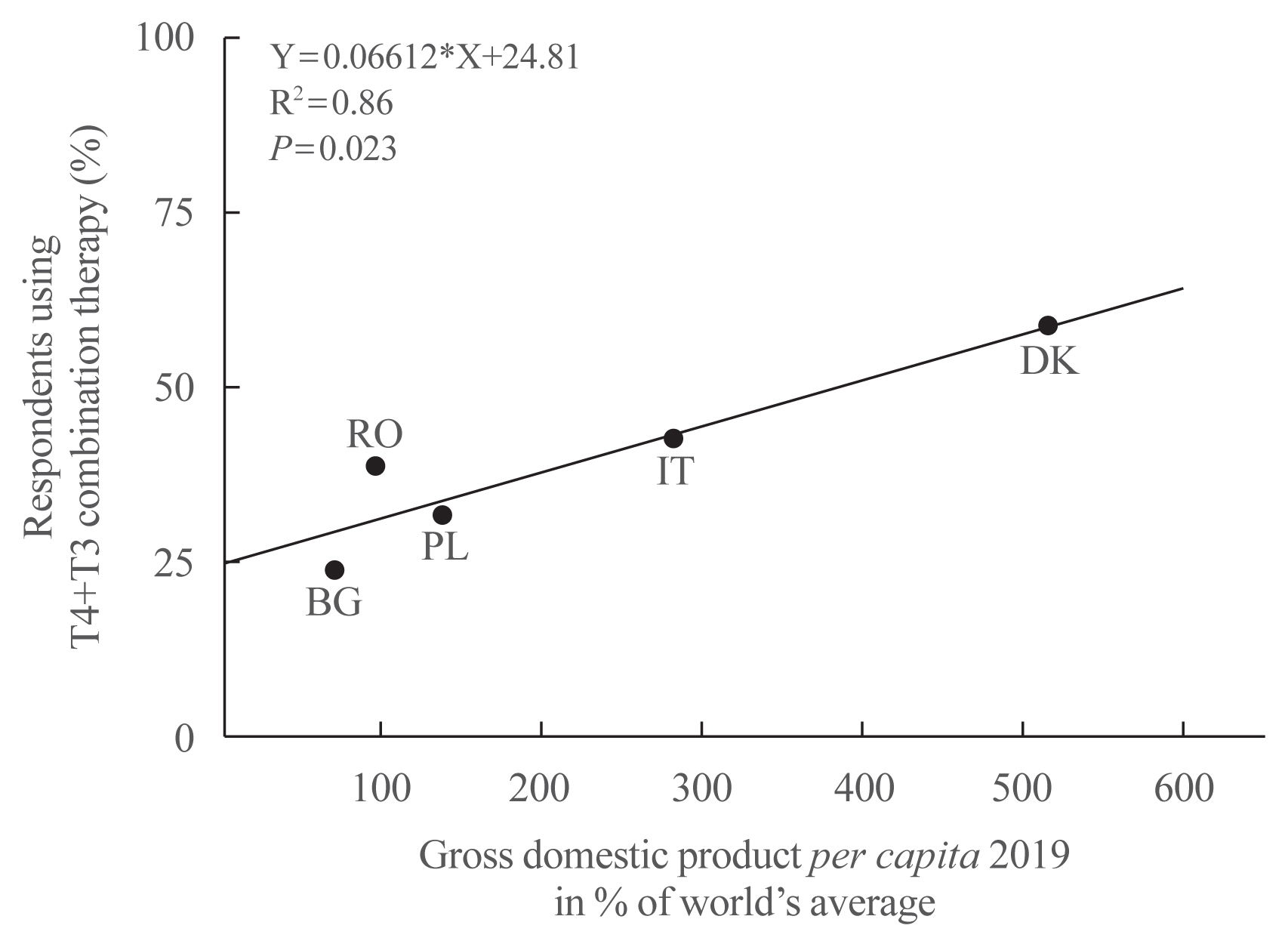

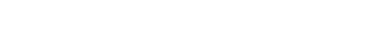

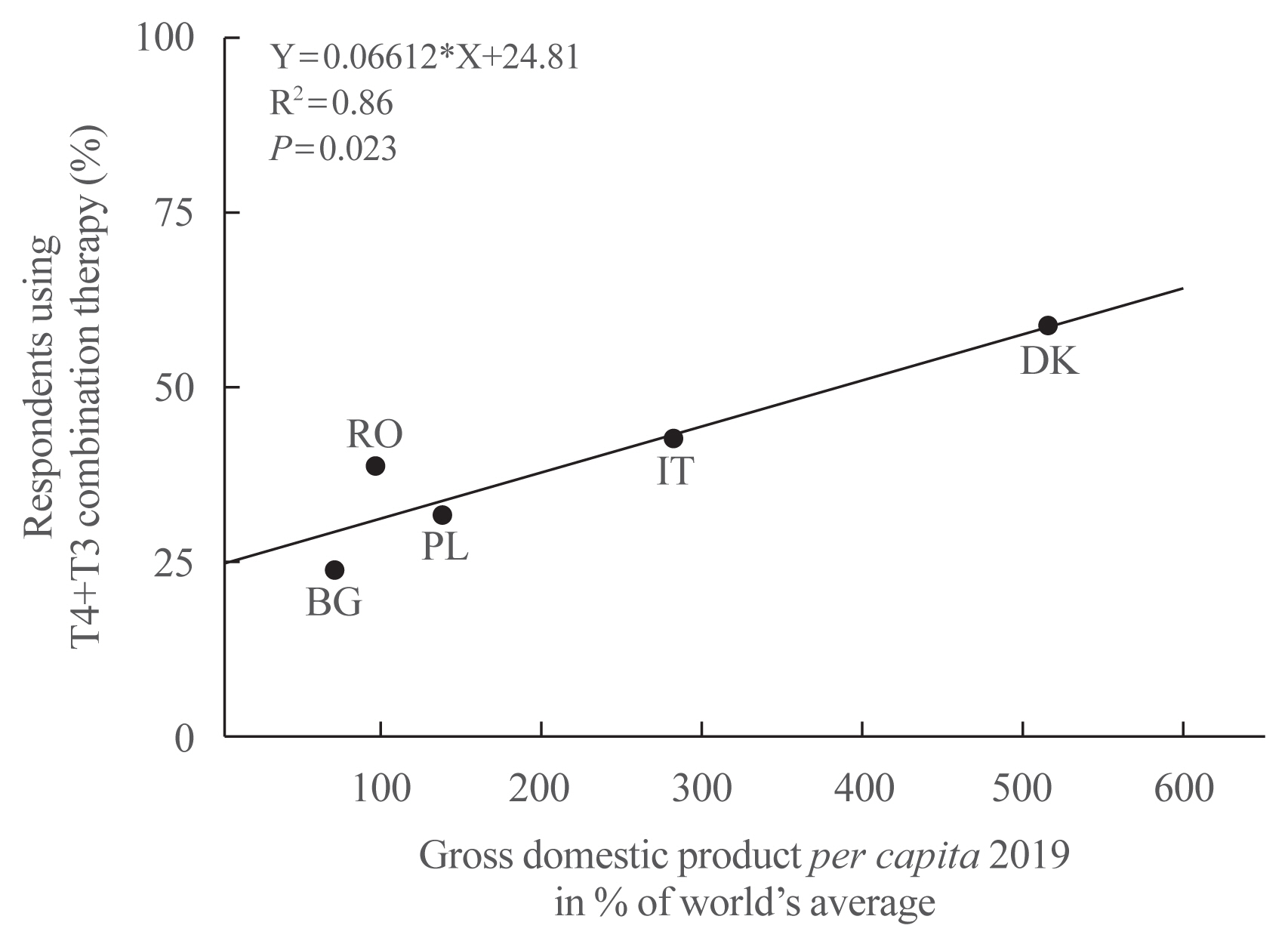

- The proportion of thyroid hormone users in the Dutch population increased from 1.87% in 2005 to 2.79% in 2011, an increase of 49% [29]. In the same period, the Dutch population size increased only by 2.1%. With regard to the various thyroid hormone preparations, the proportion of only T4 users gradually but consistently decreased from 99.05% in 2005 to 98.98% in 2011. The opposite trend was observed in T4+T3 users, the proportion of which slowly but steadily increased from 0.82% in 2005 to 0.90% in 2011; in absolute numbers, the increase was from 2,499 to 4,179 persons (67%). The proportion of only T3 users remained the same (0.13% and 0.12%). About two-thirds of prescriptions are from GPs and one-third from specialists. In a questionnaire survey among T4+T3 users in Denmark, GPs prescribed the medicine in 44% and specialists in 41% of cases, and 4% of patients bought the drugs through the internet [30]. The serum TSH level at diagnosis was <4, 4–10, 10–20, and >20 mU/L in 21%, 25%, 7%, and 14%, respectively; 32% did not remember. The number of applications for reimbursement of T4+T3 therapy was used as a surrogate for the number of new patients starting T4+T3 therapy. A 3.8-fold increase was observed from 2012 to 2014, obviously induced by the publication of a book describing experience of patients with hypothyroidism and its treatment. A United States survey in 2013 reported that overt hypothyroidism would be treated with LT4 by 99.2% of respondents and that 0.8% would use T4+T3 combination therapy [31]. Persistent hypothyroid symptoms despite achieving a target TSH on LT4 would prompt 3.6% of respondents to use T4+T3 combination therapy. In contrast, a follow-up United States survey in 2017 demonstrated that as many as 18% to 41% of physicians were willing to prescribe T4+T3 combination therapy, depending on the specific scenario [32]. Physicians from North America were found to be more likely to prescribe T4+T3 combination than physicians from outside North America (odds ratio [OR], 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2 to 2.9). A questionnaire survey called Treatment of Hypothyroidism in Europe by Specialists: an International Survey (THESIS) was done recently among members of national endocrine societies in five European countries [33–37]. Although LT4 remained the drug of choice for initiating treatment of hypothyroidism, 1% to 1.5% of respondents already used combined T4+T3 at the initiation of thyroid hormone therapy. Furthermore, 24% to 59% of respondents considered using combination therapy in patients who experience persistent hypothyroid symptoms despite a normal TSH while receiving LT4 (Table 2). Interestingly, this proportion is directly related to a given country’s economic health expressed as per capita gross domestic product (GDP): the higher the GDP, the higher the willingness to use T4+T3 combination therapy (Fig. 1).

- The overall prevalence of untreated overt and sub-clinical hypothyroidism is about 0.4% and 4.6%, respectively. The prevalence of treated hypothyroidism has increased in the last two decades, driven largely by the treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism. The prevalence of T4+T3 combination treatment is also on the rise. It is considered more frequently in countries with a high rather than low GDP.

T4+T3 COMBINATION THERAPY: A QUANTITATIVE APPROACH

Epicrisis

- In the early 2000s, persistent symptoms despite a normal TSH were reported by 5% to 15% of hypothyroid patients on LT4 treatment [5,6]. One may ask whether these prevalence figures changed over the last two decades, and whether more has been learned about the precise nature of these persistent complaints.

- The prevalence of persistent symptoms

- The prevalence of persistent symptoms has increased according to most respondents of the THESIS survey (Table 3). High prevalence figures are found in countries with a high GDP, whereas the figures are much lower in countries with a low GDP. Approximately one-third of respondents stated that the prevalence of persistent symptoms increased in the last 5 years (Table 4).

- The nature of hypothyroid symptoms

- The nature of hypothyroid symptoms tends to be non-specific and difficult to distinguish from other conditions or general suboptimal health [38]. This was nicely illustrated by a study in patients with newly diagnosed overt autoimmune hypothyroidism using a population-based case-control design [39]. Among 34 symptoms investigated, 13 symptoms were overrepresented in patients with hypothyroidism. Hypothyroid patients suffered mostly from tiredness (81%), dry skin (63%), and shortness of breath (51%). None of the individual symptoms of hypothyroidism had high likelihood ratios or diagnostic ORs [39]. The authors concluded that neither the presence nor absence of any individual hypothyroid symptom had sufficient accuracy for establishing the diagnosis of hypothyroidism.

- A Danish internet-based questionnaire study inquired about persistent symptoms on LT4 therapy before the initiation of T4+T3 combination therapy [30]. The median number of symptoms per participant was 7 (interquartile range [IQR], 5 to 8); as many as 69% of patients had ≥6 different symptoms. The frequency of these symptoms is listed in Table 5. An online survey of hypothyroid patients, posted on the American Thyroid Association website, asked the question. If you are not satisfied, indicate relevant areas you feel are affected by your thyroid treatment with LT4? [40]. The four most prevalent answers among 6,949 respondents were fatigue or energy levels (80%), weight management (70%), memory (60%), and mood (49%). These prevalence figures are in good agreement with those from the Danish online survey (Table 5) [30]. The issue of body weight might be relevant, as the preference for T4+T3 combination therapy in some of the early randomized controlled trials (RCTs) could be linked to greater weight loss [8]. In an open-label cohort study, 23 hypothyroid patients referred because of persistent symptoms despite adequate LT4 monotherapy were switched to T4+T3 combination therapy at a dose ratio of !7:1 [41]. Quality of life (QoL) assessed by the Thypro-39 composite score improved (from a baseline value of 54 towards 15 and 20 after 3 and 12 months, respectively), but there was no change in body weight. In a meta-analysis of seven blinded RCTs, the pooled prevalence rate for preference of combination therapy was 46.2% [42]. Sensitivity analysis explained the preference for T4+T3 combination in part by treatment effects on serum TSH, mood and symptoms, but not on QoL or body weight. There existed a positive association between the total daily liothyronine (LT3) dose and treatment preference [42].

- Prominent dissatisfaction

- Prominent dissatisfaction among 12,146 treated hypothyroid patients, measured on a scale from 1 (not satisfied) to 10 (very satisfied), was observed in a United States online survey done in 2017 [40]. Satisfaction was lowest in the LT4 group (median score 5; IQR, 3 to 7), intermediate in the T4+T3 group (median score 6; IQR, 3 to 8), and highest in the desiccated thyroid extract (DTE) group (median score 7; IQR, 5 to 9). Respondents taking DTE compared to those taking T4 or T4+T3 were less likely to report problems with fatigue/energy levels (−10% and −9%, respectively), weight management (−5% and −7%), mood (−11% and −11%), and memory (−8% and −11%) (all P values <0.0001). It should be emphasized that this online survey among treated hypothyroid patients was based on responses from a self-selected sample, unlikely to represent the whole United States population of hypothyroid patients, and therefore liable to multiple biases [40]. The online survey captured predominantly women, half of the respondents had changed their physician twice or more, and two-thirds believed that stress or physical comorbidities other than hypothyroidism might have caused at least part of the symptoms [40]. Similar restrictions apply to another online survey of people with treated hypothyroidism in the UK in 2019 [43]. Immediately after posting the questionnaire on the website, there was a surge of responses and the maximum number of responses allowed by the license (n=1,014) was reached within 24 hours. The sample thus represented about 0.04% of all hypothyroid patients in the UK, and was liable to bias. Satisfaction with treatment and care was recorded as a binary response (satisfied or not satisfied), and QoL was recorded on a scale of 0 to 100 (0 being worst and 100 being best) [43]. The proportion of dissatisfaction in patients treated with DTE (n=123), LT4 (n=677), and T4+T3 (n=124) was 83%, 78%, and 69%, respectively; the mean corresponding QoL was 54, 46, and 56. Multivariate analysis showed significant positive correlations between satisfaction and age, male gender, currently being under the care of a thyroid specialist, GP-prescribed DTE or T4+T3, and being fully informed by one’s GP; significant negative correlations existed between satisfaction and expectation for more support from one’s GP, negative experiences with LT4, the expectation that LT4 would resolve all symptoms, and the expectation to be referred to a specialist. QoL was positively correlated with male gender and duration of hypothyroidism, and was negatively correlated with age, ≥3 visits to a GP with symptoms of hypothyroidism before diagnosis, obtaining treatment with DTE, T4+T3, or T3 without the GP’s help, experiencing difficulties with LT4, the expectation that LT4 would resolve all symptoms, and the expectation for more support from GP. It is surprising to find that the level of satisfaction and QoL were not substantially different between users of LT4, T4+T3, and DTE, suggesting that other determinants than the thyroid hormone preparation must play a role. The authors conclude that focusing on enhancing the patient experience and clarifying expectations at diagnosis may improve satisfaction and QoL [43].

- The prevalence of persistent symptoms in LT4-treated hypothyroid patients despite a normal TSH has increased in the past 20 years, especially in countries with a high per capita GDP. The median number of persistent symptoms per patient is 7 (IQR, 5 to 8), and two-thirds of patients have ≥6 different symptoms. The four most prevalent areas of persistent complaints regard fatigue or energy levels (80% to 90%), weight management (70% to 75%), memory (60% to 80%), and mood (40% to 50%). Satisfaction with the received treatment for hypothyroidism was lowest for T4, intermediate for T4+T3, and highest for DTE in an online United States survey among patients, but in an online UK survey, satisfaction rates were not substantially different between the various thyroid hormone preparations, although QoL was lower in T4 patients than in T4+T3 or DTE patients. Both online surveys were prone to bias.

PREVALENCE AND NATURE OF PERSISTENT SYMPTOMS DESPITE A NORMAL TSH ON LT4

Epicrisis

- Endocrinologists from four European countries answered questions in the THESIS survey on what they considered the most likely or unlikely cause of persistent symptoms in LT4-treated patients with a normal TSH [34–37]. Their answers are listed in Table 6. They could choose from eight different causes. It is remarkable to see how much agreement exists among these physicians from different countries. One may assume strong agreement about a particular cause if the range of respondents who (strongly) agree about a particular cause does not overlap with the range of respondents who (strongly) disagree with that particular cause. Applying this assumption, it is clear that the inability of LT4 to restore physiological function is viewed as an unlikely cause of persistent symptoms, whereas psychosocial factors, comorbidities, unrealistic expectations, and the burden of chronic disease are considered to be more likely causes. Chronic fatigue syndrome and the burden of having to take medication are also viewed—but less strongly—as likely explanations, whereas respondents are divided about the role of inflammation due to autoimmunity.

- Low tissue T3

- The inability of LT4 to restore thyroid hormone physiology is aptly called the “low tissue T3 hypothesis” by Perros et al. [44]. The name directly refers to the basic research by Escobar-Morreale et al. [1,2], demonstrating in experimental animals that tissue T3 content could be normalized only by the combined administration of T4 and T3, not by T4 alone. There is extensive circumstantial evidence supporting this hypothesis. Hypothyroid patients replaced with LT4 require somewhat higher serum free thyroxine (FT4) levels in order to normalize serum TSH, whereas their serum free triiodothyronine (FT3) levels are somewhat lower than in euthyroid controls. Actually, 7.2% of hypothyroid patients on LT4 have FT4 levels above the upper normal limit, and 15.2% of patients have FT3 levels below the lower normal limit [45]. To compensate for the reduced thyroidal secretion of T3 (normally responsible for 20% of the daily T3 production), more T3 must be generated in extrathyroidal tissues from exogenous T4. Some tissues depend largely on serum T3 for their T3 content, whereas other tissues are capable of producing T3 themselves by deiodination of local T4. Three types of deiodinases regulate the conversion of T4 into T3 and the inactivation of T4 and T3. The expression of these enzymes varies between tissues, and it has been suggested that a polymorphism in the deiodinase 2 gene (Thr92Ala) may cause slight changes in deiodinase activity but important changes in thyroid hormone bioavailability [38]. Indeed, carriers of the Thr92Ala polymorphism demonstrate a hypothyroid-like state in the brain [46]. The co-existence of polymorphisms in the iodothyronine deiodinase 2 (DIO2) gene (rs225014=Thr92Ala) and the thyroid hormone transporter gene monocarboxylate transporter 10 (MCT10; rs17606253) significantly enhanced the preference for T4+T3 combination therapy (the preferences in patients with 0, 1, or 2 polymorphisms were 42%, 63%, and 100% respectively) [47]. In a study evaluating tissue function tests before total thyroidectomy and at 1 year postoperatively when using LT4, it was found that peripheral tissue function tests indicated mild hyperthyroidism at TSH <0.03 mU/L and mild hypothyroidism at TSH 0.3 to 5.0 mU/L; the tissues were closest to euthyroidism at TSH 0.03 to 0.3 mU/L [48]. A normal serum TSH level consequently does not necessarily indicate a euthyroid state at the tissue level [49]. In accordance, a systematic review found that clinical parameters are associated with FT4 or FT3 significantly more often than with TSH levels (50% and 23% respectively, P<0.0001) [50]. The scientific basis of the “low tissue T3 hypothesis” is thus sound, and individualized therapy for hypothyroidism could be indicated, as LT4 monotherapy may provide dissatisfaction in a subset of patients [7].

- The most remarkable finding in the questionnaire survey is that the majority of respondents disagreed that the “low tissue T3 hypothesis” plays a major causal role in persistent complaints. My feeling is that 10 years ago, it was the opposite and most specialists supported this hypothesis as a reasonable explanation of persistent symptoms. If so, what changed the perception of doctors that other factors must be involved? The very idea that there existed an alternative for T4 monotherapy became well known among hypothyroid patients, thanks to information by active thyroid patient associations in many countries and improved counseling by physicians, boosted by ongoing scientific reports that apparently strengthened the rationale for combination treatment. T4+T3 therapy became thus rather popular, and attractive to dissatisfied patients. It is against this background that the observed direct relationship between the use of T4+T3 and the per capita GDP should be considered. People in richer countries have more time and resources at their disposal to deal with their health problems, and can afford to buy the pills required for the T4+T3 combination treatment, which are not always available or reimbursed by insurance companies.

- Unrealistic expectations

- The persistence of symptoms despite ‘adequate’ LT4 monotherapy may generate dissatisfaction in patients; these patients could have great expectations about the outcomes, and could be inclined to believe it will resolve all their symptoms [43]. Epidemiological data (summarized above) demonstrate most patients treated with LT4 in the last two decades had subclinical hypothyroidism (their median TSH before treatment was 6.8 to 7.9 mU/L). A large placebo-controlled trial among patients with subclinical hypothyroidism at least 65 years of age demonstrated no apparent benefits of LT4 treatment [51]. A meta-analysis among nonpregnant adults with subclinical hypothyroidism showed the use of thyroid hormone therapy was not associated with improvements in general QoL or thyroid-related symptoms [52]. Later studies among adults aged 80 years and older with subclinical hypothyroidism confirmed that LT4 treatment, compared to placebo, was not significantly associated with improvement in hypothyroid symptoms, fatigue, or depressive symptoms [53,54]. A guideline panel including patients, clinicians, and methodologists issued in 2019 a strong recommendation against thyroid hormones in adults with subclinical hypothyroidism (which may not apply to pregnant women, patients with TSH >20 mU/L, patients with severe symptoms, or young adults ≤30 years of age) [55]. Furthermore, 36% of patients with treated subclinical hypothyroidism remain euthyroid after thyroid hormone discontinuation [56]. It is thus likely that most patients who were dissatisfied with the outcome of LT4 treatment had received LT4 because of subclinical hypothyroidism, a condition that by itself poorly responds to LT4.

- Comorbidities

- Associated autoimmune diseases occur in 14% of patients with Hashimoto’s disease and in 10% of patients with Graves’ disease [57]. Therefore the 2012 ETA guidelines already recommended excluding these comorbidities before embarking on T4+T3 combination therapy [4]. Symptoms resembling those of hypothyroidism also occur in medical conditions like chronic fatigue, anemia, stress, and changes in body weight [38]. It would be prudent to check for such conditions unrelated to the thyroid gland itself. The issue of body weight deserves special attention, as the responses to the THESIS survey disclose the use of LT4 in obese patients [33–37]. Serum TSH is significantly higher in obese patients than in normal weight controls; subclinical hypothyroidism is recorded in 13.7% of obese patients, but thyroid autoimmunity is not a major cause [58–60]. Longitudinal studies suggest that changes in the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis are side effects of increasing body weight rather than its cause, and are reduced after weight loss obtained by caloric restriction [61]. The increase in serum TSH in the absence of thyroid antibodies is likely an adaptive response. Recent European Society of Endocrinology guidelines recommend testing all patients with obesity for hypothyroidism, based on TSH; if TSH is elevated (using the same reference range as for non-obese), FT4 and thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO-Ab) should be measured [62]. The guidelines recommend against the use of thyroid hormones to treat obesity in case of normal thyroid function; they also recommend that hyperthyrotropinemia (elevated TSH and normal FT4) should not be treated in obesity with the aim of reducing body weight.

- Burden of chronic disease and burden of having to take medication

- The awareness of having a chronic disease and lifelong dependency on thyroid medication could make patients unhappy and less healthy [4,9]. Patients with persistent symptoms despite a normal serum TSH level frequently feel that their normal TSH presents a barrier to further evaluation. GPs and nurses often have inadequate knowledge of medication interactions and LT4 pharmacokinetics; information exchange is usually restricted by time and often centered on symptoms rather than patient education [63]. Positive correlations were noticed between satisfaction and being well-informed about hypothyroidism, whereas negative correlations were observed between satisfaction and expectations for more support from one’s GP [43]. Improvement of the interactions between physicians and patients could reduce barriers to optimal thyroid replacement [9].

- Somatic symptom and related disorders

- Up to 85% of respondents in the THESIS survey thought that psychosocial factors and chronic fatigue syndrome can play a causal role in persistent symptoms. These patients may have somatic symptom and related disorders (SSRD) as proposed by Perros et al. [44]. SSRD is a diagnostic classification with specific criteria described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [64,65]. It refers to persistent bodily symptoms associated with significant functional impairment, psychological distress, and high healthcare costs. The distress can concern bodily symptoms in the context of a chronic medical condition, such as hypothyroidism, or medically unexplained symptoms. It can be accompanied by anxiety or depressive disorders [44]. An individual with SSRD has a maladaptive reaction to a somatic symptom [66]. Perros et al. [44] elegantly describe the sequence of affairs: “Patients with SSRD have multiple medical consultations and inevitably thyroid function tests are ordered.” “Approximately 10% of SSRD patients may also have thyroid dysfunction, usually subclinical hypothyroidism. If patient and doctor assume the symptoms are due to hypothyroidism, LT4 is prescribed but will not be followed by symptom resolution if the actual diagnosis is SSRD. Any benefits tend to be minor and transient, leading to escalation of the dose of LT4, without consistent symptomatic improvement.” “LT4 is declared ineffective by the patient who, having consulted blogs and patient forums, may then seek treatment with T4+T3 or DTE. The patient may encounter resistance from the doctor to prescribe these treatments leading to consultations with several specialists or alternative practitioners or purchasing LT3 or DTE online. The difficulty that patients experience accessing their ‘desired’ treatment may also increase the perception of a benefit of treatment when they receive it, although symptoms usually persist. Frustration and dissatisfaction ensue and are perpetuated by the absence of effective treatment directed at the underlying cause of the symptoms.”

- Inflammation due to autoimmunity

- A cross-sectional study among patients with autoimmune hypothyroidism observed that TPO-Ab levels (but not TSH, FT4, or FT3) are related to goiter symptoms, depressivity, and anxiety [67]. A meta-analysis observed an association between autoimmune thyroiditis and depression (OR, 3.56; 95% CI, 2.14 to 5.94) or anxiety (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.40 to 3.85) [68]. LT4-treated patients with persistent symptoms despite a normal TSH and high TPO-Ab were randomized to receive total thyroidectomy or continuation of LT4 treatment; QoL and fatigue improved after total thyroidectomy. After 1.5 years, median TPO-Ab values were reduced from 2,232 to 152 kU/L in the surgical group, and from 2,052 to 1,300 kU/L in the medical group [69]. The autoimmune neuroinflammation hypothesis is the only cause of persistent symptoms shown in Table 5, for which there existed a complete overlap between respondents agreeing or not agreeing with this particular cause (Table 5). Obviously, respondents felt quite uncertain about this cause. However, the hypothesis remains plausible, as strengthened by a recent systematic review [70].

- Persistent symptoms in LT4-treated patients despite a normal TSH can have several causes. Whereas the “low tissue T3” hypothesis was dominant a decade ago, nowadays many other causes are thought to be likely involved including unrealistic patient expectations, comorbidities, and the SSRD hypothesis. The multifactorial nature of persistent symptoms has evolved against the background of “hype” surrounding T4+T3 combination treatment in many countries (“hype” is something that, especially thanks to efforts of the media, emerges as a fashion or sensation in a specific public).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS FOR PERSISTENT SYMPTOMS ON LT4

Epicrisis

- The diversity of causes for persistent symptoms should be taken into account in the management plan.

- Mitigate unrealistic expectations

- Can the occurrence of persistent symptoms on LT4 treatment be avoided? Probably so, at least to a certain extent, especially in patients who had unrealistic expectations about the outcome of LT4 treatment. We have seen an increase in the prevalence of treated hypothyroidism in the last decades, mostly due to an increase in the prevalence of treated subclinical hypothyroidism [27,28]. More recently, it has become clear from placebo-controlled RCTs that the use of thyroid hormone in subclinical hypothyroidism is not associated with improvements in QoL or thyroid-related symptoms [52]. Better counseling of patients and more information on what might be expected from treatment before initiating LT4, might reduce unrealistic expectations and the chance of persisting symptoms.

- Check for comorbidities

- Persistent symptoms are sometimes caused by associated autoimmune diseases, which in view of their high prevalence in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (13.7%) should be given more attention [57]. The rising worldwide prevalence of obesity is of concern in this context, because 14% of obese patients have subclinical hypothyroidism, often without thyroid antibodies [58–60]. Recent guidelines recommend not to treat isolated hyperthyrotropinemia in obese patients with thyroid hormone if the goal of treatment is reduction of body weight [62]. This advice will prevent dissatisfaction with the outcome of LT4 treatment, as a recent meta-analysis showed that treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism does not improve clinical symptoms such as overweight [52].

- Improve doctor-patient relationship

- Many studies report that dissatisfaction with LT4 outcomes in hypothyroid patients is related to previous negative experiences with health care workers [32,38,40,43,44]. For instance, dissatisfied patients had often paid ≥3 visits to their GP with symptoms before the diagnosis of hypothyroidism was made, had changed their GP ≥2 times, were not fully informed or had expected more support from their doctor. Doctors are instrumental in helping patients to cope with the burden of having a chronic disease and the burden of taking daily medication. Focusing on enhancing the patient experience and clarifying expectations at diagnosis may improve satisfaction and QoL [43].

- Explore cognitive behavioral therapy and a collaborative care model

- Hypothyroid women on LT4 (score <60 on the SF36 QoL questionnaire) were randomized to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (8 weekly sessions each lasting 90 minutes, in a group of 12) or no specific intervention; CBT improved scores for emotional health, energy, and general health to a greater extent than in controls [71]. CBT might be feasible as treatment for somatic symptom disorder [72], and recommendations have been published for core outcome domains in clinical trials on somatic symptom disorder [73]. A collaborative care model combining training with psychiatric consultation in the general practice setting could also be an effective intervention in the treatment of persistent medically unexplained symptoms [74]. It is obvious that much has to be learned about this approach to persistent symptoms in LT4-treated hypothyroid patients.

- Consider T4+T3 combination therapy

- To validate the “low tissue T3” hypothesis, more and better-designed RCTs should be done. The RCTs carried out so far did not provide conclusive answers, as most if not all studies could be criticized for the following reasons: (1) heterogeneous patient population including hypothyroid patients due to Hashimoto’s disease or thyroidectomy/131I therapy (for thyroid cancer, multinodular goiter, or Graves’ disease); (2) inclusion of patients irrespective of persistent symptoms; (3) too small a sample size; (4) wide variation in T4+T3 dosages in combination treatment; and (5) different primary and secondary outcomes [8,9]. To promote discussions about an optimal study design, the American, European and British thyroid associations have recently published a consensus document, which is very helpful [75]. My own recommendations for a new RCT comparing T4 monotherapy versus T4+T3 combination therapy would be:

Use more strict selection criteria: The study should include hypothyroid patients on a stable dose of LT4 for at least 6 months, with persistent symptoms and a normal serum TSH level, in whom associated autoimmune comorbidities have been ruled out. I would exclude patients who initially were treated because of subclinical hypothyroidism, as treatment is unlikely to improve their symptoms [52]. This probably means excluding patients who used <1.2 μg/kg/day LT4 as recommended by the consensus panel [75].

Choose a randomized, double-blind, parallel study design: The double-blind design should be ensured by having placebo pills besides the LT4 pills in the T4 monotherapy arm. A crossover study design has the inherent risk of a carry-over effect. The duration of the intervention should be sufficiently long (≥6 months), because we do not know how long it will take before tissue T3 content is normalized.

Calculate the sample size: It should be high enough to allow a subanalysis between carriers of specific polymorphisms (e.g., DIO2, MCT8, MCT10, OATP1C1) and noncarriers [76, 77]. One should therefore know the prevalence of these polymorphisms. The Ala/Ala genotype of the DIO2 Thr92Ala polymorphism is present in 11% of both LT4 users and the general population, although without effects on differences in thyroid hormone parameters, health-related QoL, and cognitive functioning [78]. It could be difficult to achieve the required large sample size. In Norwegian women in the period from 1995–1997 to 2006–2008, the prevalence of untreated overt hypothyroidism decreased by 84% (from 0.75% to 0.16%) and that of untreated subclinical hypothyroidism decreased by 64% (from 3.0% to 1.1%), whereas that of treated hypothyroidism increased by 60% (from 5.0% to 8.0%); the prevalence of any form of hypothyroidism remained essentially similar (9% in women and 3% in men) [79].

Calculate T4 and T3 dosages of combination treatment: This is a controversial area. Consensus exists that the daily T3 dose should be split into two administrations (as long as a slow-release T3 preparation is not available). Some physicians just replace part of the usual T4 dose by T3 at a substitution ratio of 3:1 (e.g., 25 μg of T4 is replaced by 7.5 μg of T3) [80]. A daily dose of 150 μg of T4 during monotherapy would thus be transferred into 125 μg of T4+7.5 μg of T3 during combination therapy (i.e., a dose ratio of 17:1). I prefer this dose ratio, which is closest to the physiological T4 to T3 secretion ratio of 16:1 by the thyroid gland itself [81]. Most studies in the literature used lower T4:T3 dose ratios, in the order of 5:1 to 10:1, which might be more effective but also liable to more side effects [1]. Adaptation of the combination dosage should be considered if serum TSH values are encountered outside the reference range. It makes sense not to change T4 and T3 doses simultaneously; the ETA guidelines recommend to adapt first the daily T3 dose [1]. Maintenance of a normal serum TSH level is prudent because two large independent population studies over the past 2 years have shown that mortality of hypothyroid patients treated with LT4 is increased when the serum TSH exceeds or is reduced outside the normal reference range [82]. Residual thyroid function (RTF) might be a key factor in the success of combination therapy. A recent algorithm estimates RTF and then optimizes T4+T3 dosages, resulting in T4:T3 dose ratios of 8:1 to 13:1 with escalating RTF [83].

Define primary and secondary outcomes: It would be advantageous if RCTs would use the same primary outcome. A suitable candidate is the thyroid-specific and well-validated QoL questionnaire, the ThyPRO [84]. This patient-reported outcome instrument consists of 84 items summarized in 13 scales; each item is rated on a 0–4 Likert scale to yield thirteen 0–100 scales, with higher scores indicating worse health status. The scores for each scale are nicely visualized on a ThyPRO radar plot. The ThyPRO has good cross-cultural validity; the shortened ThyPRO-39, which is now available in many languages, might be preferred [41,85]. A secondary outcome should be patient preference for monotherapy or combination therapy. A variety of biologic markers, including metabolic, cardiovascular, cognitive, and musculoskeletal parameters, can also be recorded.

Incorporate safety precautions: Hyperthyroid symptoms, tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, and decreased bone density and fractures would all be relevant, and should be assessed [75]. Fortunately, it is possible using T4+T3 combination therapy to keep serum TSH, FT4, and FT3 within their normal range in ≥90% of patients [86]. Observational studies lasting 9 to 17 years found no increased risk of cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, or fractures in patients using T3 compared to patients using T4 [87,88]. The use of LT3 did not lead to increased breast cancer or any cancer incidence and mortality compared with LT4 use [89]. There was only an increased incident use of antipsychotic medication during follow-up in T3 users [87].

- Improving the doctor-patient relationship seems most relevant, besides mitigating unrealistic expectations and looking for comorbidities. CBT is promising in patients with somatic symptom disorder. To validate the “low tissue T3” hypothesis, there is no alternative but to conduct more and better-designed RCTs comparing T4+T3 combination therapy and T4 monotherapy. The 2012 ETA guidelines for individual T4+T3 treatment are still well-grounded.

HOW TO MAKE PROGRESS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PERSISTENT SYMPTOMS ON LT4 DESPITE A NORMAL TSH?

Epicrisis

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Article information

| Country | Period | Prevalence of overt hypothyroidism, % | Prevalence subclinical hypothyroidism, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA [11] | 1988–1994 | 0.3 | 4.6 |

| USA [12] | 1995 | 0.4 | 8.5 |

| Europe [13] | 1975–2012 | 0.6 | 4.6 |

| Europe [14] | 2008–2018 | 0.6 | 4.1 |

| Spain [15] | 2009–2010 | 0.3 | 4.6 |

| Japan [16] | 2005–2006 | 0.7 | 5.8 |

| Korea [17,18] | 2013–2015 | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| Country | Responders, n (%) | T4 drug of choice, %a | T4+T3 use considered, %b | GDP 2019 per capita in $ (% of world’s average)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy [33] | 797 (39) | 99 | 43 | 35,614 (282) |

| Denmark [34] | 152 (31) | 94 | 59 | 65,147 (516) |

| Romania [35] | 316 (42) | 99 | 39 | 12,131 (96) |

| Poland [36] | 423 (55) | 96 | 32 | 17,387 (138) |

| Bulgaria [37] | 120 (95) | 96 | 24 | 9,026 (71) |

THESIS, Treatment of Hypothyroidism in Europe by Specialists: an International Survey; T4, thyroxine; T3, triiodothyronine; GDP, gross domestic product.

a Preference at initiation of thyroid hormone replacement therapy;

b Combination therapy considered for use in patients with persistent symptoms despite a normal thyroid stimulating hormone on levothyroxine;

c GDP per capita in 2019 in US dollars, with % of world’s average GDP in parentheses (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD).

| Country | Frequency of persistent symptoms as estimated by respondents, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5% | 6%–10% | 11%–30% | >30% | Not sure | |

| Denmark [34] | 23.0 | 37.5 | 1.3 | 11.2 | 27 |

| Romania [35] | 46.9 | 37.9 | - | - | - |

| Poland [36] | 33.1 | 28.8 | - | - | - |

| Bulgaria [37] | 41.7 | 34.2 | 6.6 | 2.5 | 15 |

| Country | Changes in frequency of persistent symptoms despite a normal TSH over the last 5 years as estimated by respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase last 5 yr, % | No change last 5 yr, % | Decrease last 5 yr, % | Not sure, % | |

| Denmark [34] | 58.6 | 13.8 | 6.6 | 21.1 |

| Romania [35] | - | 31.8 | 24.1 | - |

| Poland [36] | 36.4 | 28.1 | - | - |

| Bulgaria [37] | 26.6 | 35.0 | 14.2 | 24.2 |

| Possible cause of persistent symptoms despite a normal TSH on LT4 | Proportion of respondentsb | |

|---|---|---|

| (Strongly) agree, % | (Strongly) disagree, % | |

| Inability of LT4 to restore physiology | 12–20 | 53–63 |

| Psychosocial factors | 67–82 | 3–14 |

| Comorbidities | 42–85 | 5–16 |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 24–77 | 7–21 |

| Patient unrealistic expectation | 58–72 | 6–19 |

| Inflammation due to autoimmunity | 15–48 | 20–41 |

| Burden of chronic disease | 40–85 | 2–24 |

| Burden of having to take medication | 30–44 | 15–26 |

- 1. Escobar-Morreale HF, Obregon MJ, Escobar del Rey F, Morreale de Escobar G. Replacement therapy for hypothyroidism with thyroxine alone does not ensure euthyroidism in all tissues, as studied in thyroidectomized rats. J Clin Invest 1995;96:2828–38.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Escobar-Morreale HF, del Rey FE, Obregon MJ, de Escobar GM. Only the combined treatment with thyroxine and triiodothyronine ensures euthyroidism in all tissues of the thyroidectomized rat. Endocrinology 1996;137:2490–502.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Fraser A, Nahshoni E, Weizman A, Leibovici L. Thyroxine-triiodothyronine combination therapy versus thyroxine monotherapy for clinical hypothyroidism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:2592–9.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Wiersinga WM, Duntas L, Fadeyev V, Nygaard B, Vanderpump MP. 2012 ETA guidelines: the use of L-T4 + L-T3 in the treatment of hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 2012;1:55–71.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Saravanan P, Chau WF, Roberts N, Vedhara K, Greenwood R, Dayan CM. Psychological well-being in patients on ‘adequate’ doses of l-thyroxine: results of a large, controlled community-based questionnaire study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;57:577–85.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Wekking EM, Appelhof BC, Fliers E, Schene AH, Huyser J, Tijssen JG, et al. Cognitive functioning and well-being in euthyroid patients on thyroxine replacement therapy for primary hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;153:747–53.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Ettleson MD, Bianco AC. Individualized therapy for hypothyroidism: is T4 enough for everyone? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:e3090–104.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Wiersinga WM. Paradigm shifts in thyroid hormone replacement therapies for hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014;10:164–74.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Wiersinga WM. Therapy of endocrine disease: T4 + T3 combination therapy: is there a true effect? Eur J Endocrinol 2017;177:R287–96.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, Gutierrez-Buey G, Lazarus JH, Dayan CM, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018;14:301–16.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, Hannon WH, Gunter EW, Spencer CA, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:489–99.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:526–34.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Garmendia Madariaga A, Santos Palacios S, Guillen-Grima F, Galofre JC. The incidence and prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in Europe: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:923–31.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Mendes D, Alves C, Silverio N, Batel Marques F. Prevalence of undiagnosed hypothyroidism in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Thyroid J 2019;8:130–43.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Valdes S, Maldonado-Araque C, Lago-Sampedro A, Lillo JA, Garcia-Fuentes E, Perez-Valero V, et al. Population-based national prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in Spain and associated factors: Di@bet.es Study. Thyroid 2017;27:156–66.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Kasagi K, Takahashi N, Inoue G, Honda T, Kawachi Y, Izumi Y. Thyroid function in Japanese adults as assessed by a general health checkup system in relation with thyroid-related antibodies and other clinical parameters. Thyroid 2009;19:937–44.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Chung JH. Evaluation of thyroid hormone levels and urinary iodine concentrations in Koreans based on the data from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey VI (2013 to 2015). Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2018;33:160–3.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 18. Kim WG, Kim WB, Woo G, Kim H, Cho Y, Kim TY, et al. Thyroid stimulating hormone reference range and prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in the Korean population: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013 to 2015. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2017;32:106–14.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Leese GP, Flynn RV, Jung RT, Macdonald TM, Murphy MJ, Morris AD. Increasing prevalence and incidence of thyroid disease in Tayside, Scotland: the Thyroid Epidemiology Audit and Research Study (TEARS). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:311–6.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999–2012. JAMA 2015;314:1818–31.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Giorda CB, Carna P, Romeo F, Costa G, Tartaglino B, Gnavi R. Prevalence, incidence and associated comorbidities of treated hypothyroidism: an update from a European population. Eur J Endocrinol 2017;176:533–42.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Razvi S, Korevaar TIM, Taylor P. Trends, determinants, and associations of treated hypothyroidism in the United Kingdom, 2005–2014. Thyroid 2019;29:174–82.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Ingoe L, Phipps N, Armstrong G, Rajagopal A, Kamali F, Razvi S. Prevalence of treated hypothyroidism in the community: analysis from general practices in North-East England with implications for the United Kingdom. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2017;87:860–4.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Johansen ME, Marcinek JP, Doo Young Yun J. Thyroid hormone use in the United States, 1997–2016. J Am Board Fam Med 2020;33:284–8.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Maraka S, Ospina NS, Montori VM, Brito JP. Levothyroxine overuse: time for an about face? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:246–8.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Statista. Leading chemical drugs dispenses in England 2019 [Internet] New York: Statista Inc.; 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.statista.com .

- 27. Taylor PN, Iqbal A, Minassian C, Sayers A, Draman MS, Greenwood R, et al. Falling threshold for treatment of borderline elevated thyrotropin levels-balancing benefits and risks: evidence from a large community-based study. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:32–9.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Medici BB, Nygaard B, la Cour JL, Grand MK, Siersma V, Nicolaisdottir DR, et al. Changes in prescription routines for treating hypothyroidism between 2001 and 2015: an observational study of 929,684 primary care patients in Copenhagen. Thyroid 2019;29:910–9.ArticlePubMed

- 29. de Jong NW, Baljet GM. Use of T4, T4 + T3, and T3 in the Dutch population in the period 2005–2011. Eur Thyroid J 2012;1:135–6.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Michaelsson LF, Medici BB, la Cour JL, Selmer C, Roder M, Perrild H, et al. Treating hypothyroidism with thyroxine/triiodothyronine combination therapy in Denmark: following guidelines or following trends? Eur Thyroid J 2015;4:174–80.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. Burch HB, Burman KD, Cooper DS, Hennessey JV. A 2013 survey of clinical practice patterns in the management of primary hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:2077–85.ArticlePubMed

- 32. Jonklaas J, Tefera E, Shara N. Prescribing therapy for hypothyroidism: influence of physician characteristics. Thyroid 2019;29:44–52.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Negro R, Attanasio R, Nagy EV, Papini E, Perros P, Hegedus L. Use of thyroid hormones in hypothyroid and euthyroid patients: the 2019 Italian survey. Eur Thyroid J 2020;9:25–31.ArticlePubMed

- 34. Riis KR, Frolich JS, Hegedus L, Negro R, Attanasio R, Nagy EV, et al. Use of thyroid hormones in hypothyroid and euthyroid patients: a 2020 THESIS questionnaire survey of members of the Danish Endocrine Society. J Endocrinol Invest 2021;44:2435–44.Article

- 35. Niculescu DA, Attanasio R, Hegedus L, Nagy EV, Negro R, Papini E, et al. Use of thyroid hormones in hypothyroid and euthyroid patients: a Thesis* questionnaire survey of Romanian physicians *Thesis: treatment of hypothyroidism in Europe by specialists: an international survey. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar) 2020;16:462–9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 36. Bednarczuk T, Attanasio R, Hegedus L, Nagy EV, Negro R, Papini E, et al. Use of thyroid hormones in hypothyroid and euthyroid patients: a Thesis* questionnaire survey of Polish physicians. *Thesis: treatment of hypothyroidism in Europe by specialists. An international survey. Endokrynol Pol 2021;72:357–65.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Borissova AMI, Boyanov MA, Attanasio R, Hegedus L, Nagy E, Negro R, et al. Use of thyroid hormones in hypothyroid and euthyroid patients: a THESIS* questionnaire survey of Bulgarian physicians. Endocrinologia 2020;25:299–309.

- 38. Razvi S, Mrabeti S, Luster M. Managing symptoms in hypothyroid patients on adequate levothyroxine: a narrative review. Endocr Connect 2020;9:R241–50.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 39. Carle A, Pedersen IB, Knudsen N, Perrild H, Ovesen L, Laurberg P. Hypothyroid symptoms and the likelihood of overt thyroid failure: a population-based case-control study. Eur J Endocrinol 2014;171:593–602.ArticlePubMed

- 40. Peterson SJ, Cappola AR, Castro MR, Dayan CM, Farwell AP, Hennessey JV, et al. An online survey of hypothyroid patients demonstrates prominent dissatisfaction. Thyroid 2018;28:707–21.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 41. Michaelsson LF, la Cour JL, Medici BB, Watt T, Faber J, Nygaard B. Levothyroxine/liothyronine combination therapy and quality of life: is it all about weight loss? Eur Thyroid J 2018;7:243–50.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 42. Akirov A, Fazelzad R, Ezzat S, Thabane L, Sawka AM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient preferences for combination thyroid hormone treatment for hypothyroidism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:477.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 43. Mitchell AL, Hegedus L, Zarkovic M, Hickey JL, Perros P. Patient satisfaction and quality of life in hypothyroidism: an online survey by the British thyroid foundation. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2021;94:513–20.ArticlePubMed

- 44. Perros P, Van Der Feltz-Cornelis C, Papini E, Nagy EV, Weetman AP, Hegedus L. The enigma of persistent symptoms in hypothyroid patients treated with levothyroxine: a narrative review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2021 Mar 30 [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.14473 .Article

- 45. Gullo D, Latina A, Frasca F, Le Moli R, Pellegriti G, Vigneri R. Levothyroxine monotherapy cannot guarantee euthyroidism in all athyreotic patients. PLoS One 2011;6:e22552.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 46. Jo S, Fonseca TL, Bocco BMLC, Fernandes GW, McAninch EA, Bolin AP, et al. Type 2 deiodinase polymorphism causes ER stress and hypothyroidism in the brain. J Clin Invest 2019;129:230–45.ArticlePubMed

- 47. Carle A, Faber J, Steffensen R, Laurberg P, Nygaard B. Hypothyroid patients encoding combined MCT10 and DIO2 gene polymorphisms may prefer L-T3 + L-T4 combination treatment: data using a blind, randomized, clinical study. Eur Thyroid J 2017;6:143–51.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 48. Ito M, Miyauchi A, Hisakado M, Yoshioka W, Ide A, Kudo T, et al. Biochemical markers reflecting thyroid function in athyreotic patients on levothyroxine monotherapy. Thyroid 2017;27:484–90.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 49. Peterson SJ, McAninch EA, Bianco AC. Is a normal TSH synonymous with “euthyroidism” in levothyroxine monotherapy? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:4964–73.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 50. Fitzgerald SP, Bean NG, Falhammar H, Tuke J. Clinical parameters are more likely to be associated with thyroid hormone levels than with thyrotropin levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid 2020;30:1695–709.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 51. Stott DJ, Rodondi N, Kearney PM, Ford I, Westendorp RGJ, Mooijaart SP, et al. Thyroid hormone therapy for older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2534–44.PubMed

- 52. Feller M, Snel M, Moutzouri E, Bauer DC, de Montmollin M, Aujesky D, et al. Association of thyroid hormone therapy with quality of life and thyroid-related symptoms in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2018;320:1349–59.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 53. Mooijaart SP, Du Puy RS, Stott DJ, Kearney PM, Rodondi N, Westendorp RGJ, et al. Association between levothyroxine treatment and thyroid-related symptoms among adults aged 80 years and older with subclinical hypothyroidism. JAMA 2019;322:1977–86.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 54. Wildisen L, Feller M, Del Giovane C, Moutzouri E, Du Puy RS, Mooijaart SP, et al. Effect of levothyroxine therapy on the development of depressive symptoms in older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism: an ancillary study of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2036645.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 55. Bekkering GE, Agoritsas T, Lytvyn L, Heen AF, Feller M, Moutzouri E, et al. Thyroid hormones treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2019;365:l2006.ArticlePubMed

- 56. Burgos N, Toloza FJK, Singh Ospina NM, Brito JP, Salloum RG, Hassett LC, et al. Clinical outcomes after discontinuation of thyroid hormone replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid 2021;31:740–51.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 57. Boelaert K, Newby PR, Simmonds MJ, Holder RL, Carr-Smith JD, Heward JM, et al. Prevalence and relative risk of other autoimmune diseases in subjects with autoimmune thyroid disease. Am J Med 2010;123:183.Article

- 58. Rotondi M, Leporati P, La Manna A, Pirali B, Mondello T, Fonte R, et al. Raised serum TSH levels in patients with morbid obesity: is it enough to diagnose subclinical hypothyroidism? Eur J Endocrinol 2009;160:403–8.ArticlePubMed

- 59. Valdes S, Maldonado-Araque C, Lago-Sampedro A, Lillo-Munoz JA, Garcia-Fuentes E, Perez-Valero V, et al. Reference values for TSH may be inadequate to define hypothyroidism in persons with morbid obesity: Di@bet.es study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;25:788–93.ArticlePubMed

- 60. van Hulsteijn LT, Pasquali R, Casanueva F, Haluzik M, Ledoux S, Monteiro MP, et al. Prevalence of endocrine disorders in obese patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol 2020;182:11–21.ArticlePubMed

- 61. Kok P, Roelfsema F, Langendonk JG, Frolich M, Burggraaf J, Meinders AE, et al. High circulating thyrotropin levels in obese women are reduced after body weight loss induced by caloric restriction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:4659–63.ArticlePubMed

- 62. Pasquali R, Casanueva F, Haluzik M, van Hulsteijn L, Ledoux S, Monteiro MP, et al. European Society of Endocrinology clinical practice guideline: endocrine work-up in obesity. Eur J Endocrinol 2020;182:G1–32.ArticlePubMed

- 63. Dew R, King K, Okosieme OE, Pearce SH, Donovan G, Taylor PN, et al. Attitudes and perceptions of health professionals towards management of hypothyroidism in general practice: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019970.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 64. American Psychiatric Association, Division of Research. Highlights of changes from DSM-IV to DSM-5: somatic symptom and related disorders. Focus 2013;11:525–7.

- 65. Regier DA, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. The DSM-5: classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry 2013;12:92–8.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 66. van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Houdenhove B. DSM-5: from ‘somatoform disorders’ to ‘somatic symptom and related disorders’. Tijdschr Psychiatr 2014;56:182–6.PubMed

- 67. Watt T, Hegedus L, Bjorner JB, Groenvold M, Bonnema SJ, Rasmussen AK, et al. Is thyroid autoimmunity per se a determinant of quality of life in patients with autoimmune hypothyroidism? Eur Thyroid J 2012;1:186–92.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 68. Siegmann EM, Muller HHO, Luecke C, Philipsen A, Kornhuber J, Gromer TW. Association of depression and anxiety disorders with autoimmune thyroiditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2018;75:577–84.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 69. Guldvog I, Reitsma LC, Johnsen L, Lauzike A, Gibbs C, Carlsen E, et al. Thyroidectomy versus medical management for euthyroid patients with Hashimoto disease and persisting symptoms: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:453–64.ArticlePubMed

- 70. Groenewegen KL, Mooij CF, van Trotsenburg ASP. Persisting symptoms in patients with Hashimoto’s disease despite normal thyroid hormone levels: does thyroid autoimmunity play a role? A systematic review. J Transl Autoimmun 2021;4:100101.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 71. Rezaei S, Abedi P, Maraghi E, Hamid N, Rashidi H. The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on quality of life in women with hypothyroidism in the reproductive age: a randomized controlled trial. Thyroid Res 2020;13:6.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 72. Verdurmen MJ, Videler AC, Kamperman AM, Khasho D, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Cognitive behavioral therapy for somatic symptom disorders in later life: a prospective comparative explorative pilot study in two clinical populations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2017;13:2331–9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 73. Rief W, Burton C, Frostholm L, Henningsen P, Kleinstauber M, Kop WJ, et al. Core outcome domains for clinical trials on somatic symptom disorder, bodily distress disorder, and functional somatic syndromes: European network on somatic symptom disorders recommendations. Psychosom Med 2017;79:1008–15.ArticlePubMed

- 74. van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Oppen P, Ader HJ, van Dyck R. Randomised controlled trial of a collaborative care model with psychiatric consultation for persistent medically unexplained symptoms in general practice. Psychother Psychosom 2006;75:282–9.ArticlePubMed

- 75. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Cappola AR, Celi FS, Fliers E, Heuer H, et al. Evidence-based use of levothyroxine/liothyronine combinations in treating hypothyroidism: a consensus document. Eur Thyroid J 2021;10:10–38.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 76. McAninch EA, Jo S, Preite NZ, Farkas E, Mohacsik P, Fekete C, et al. Prevalent polymorphism in thyroid hormone-activating enzyme leaves a genetic fingerprint that underlies associated clinical syndromes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:920–33.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 77. Porcelli T, Salvatore D. Targeting the right population for T3 + T4 combined therapy: where are we now and where to next? Endocrine 2020;69:244–8.ArticlePubMed

- 78. Wouters HJ, van Loon HC, van der Klauw MM, Elderson MF, Slagter SN, Kobold AM, et al. No effect of the Thr92Ala polymorphism of deiodinase-2 on thyroid hormone parameters, health-related quality of life, and cognitive functioning in a large population-based cohort study. Thyroid 2017;27:147–55.ArticlePubMed

- 79. Asvold BO, Vatten LJ, Bjoro T. Changes in the prevalence of hypothyroidism: the HUNT Study in Norway. Eur J Endocrinol 2013;169:613–20.ArticlePubMed

- 80. Celi FS, Zemskova M, Linderman JD, Babar NI, Skarulis MC, Csako G, et al. The pharmacodynamic equivalence of levothyroxine and liothyronine: a randomized, double blind, cross-over study in thyroidectomized patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72:709–15.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 81. Pilo A, Iervasi G, Vitek F, Ferdeghini M, Cazzuola F, Bianchi R. Thyroidal and peripheral production of 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine in humans by multicompartmental analysis. Am J Physiol 1990;258(4 Pt 1):E715–26.ArticlePubMed

- 82. Perros P, Nirantharakumar K, Hegedus L. Recent evidence sets therapeutic targets for levothyroxine-treated patients with primary hypothyroidism based on risk of death. Eur J Endocrinol 2021;184:C1–3.ArticlePubMed

- 83. DiStefano J 3rd, Jonklaas J. Predicting optimal combination LT4 + LT3 therapy for hypothyroidism based on residual thyroid function. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:746.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 84. Winther KH, Cramon P, Watt T, Bjorner JB, Ekholm O, Feldt-Rasmussen U, et al. Disease-specific as well as generic quality of life is widely impacted in autoimmune hypothyroidism and improves during the first six months of levothyroxine therapy. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156925.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 85. Watt T, Barbesino G, Bjorner JB, Bonnema SJ, Bukvic B, Drummond R, et al. Cross-cultural validity of the thyroid-specific quality-of-life patient-reported outcome measure, ThyPRO. Qual Life Res 2015;24:769–80.ArticlePubMed

- 86. Tariq A, Wert Y, Cheriyath P, Joshi R. Effects of long-term combination LT4 and LT3 therapy for improving hypothyroidism and overall quality of life. South Med J 2018;111:363–9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 87. Leese GP, Soto-Pedre E, Donnelly LA. Liothyronine use in a 17 year observational population-based study: the tears study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2016;85:918–25.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 88. Idrees T, Palmer S, Maciel RMB, Bianco AC. Liothyronine and desiccated thyroid extract in the treatment of hypothyroidism. Thyroid 2020;30:1399–413.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 89. Planck T, Hedberg F, Calissendorff J, Nilsson A. Liothyronine use in hypothyroidism and its effects on cancer and mortality. Thyroid 2021;31:732–9.ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Association of DIO2 and MCT10 Polymorphisms With Persistent Symptoms in LT4-Treated Patients in the UK Biobank

Christian Zinck Jensen, Jonas Lynggaard Isaksen, Gustav Ahlberg, Morten Salling Olesen, Birte Nygaard, Christina Ellervik, Jørgen Kim Kanters

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.2024; 109(2): e613. CrossRef - Quality of life, daily functioning, and symptoms in hypothyroid patients on thyroid replacement therapy: A Dutch survey

Ellen Molewijk, Eric Fliers, Koen Dreijerink, Ad van Dooren, Rob Heerdink

Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology.2024; 35: 100330. CrossRef - Use of thyroid hormones in hypothyroid and euthyroid patients: A survey of members of the Endocrine Society of Australia

Nicole Lafontaine, Suzanne J. Brown, Petros Perros, Enrico Papini, Endre V. Nagy, Roberto Attanasio, Laszlo Hegedüs, John P. Walsh

Clinical Endocrinology.2024; 100(5): 477. CrossRef - Use of Thyroid Hormones in Hypothyroid and Euthyroid Patients: A THESIS questionnaire survey of members of the Irish Endocrine Society

Mohamad Mustafa, Elsheikh Ali, Anne McGowan, Laura McCabe, Laszlo Hegedüs, Roberto Attanasio, Endre V. Nagy, Enrico Papini, Petros Perros, Carla Moran

Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -).2023; 192(5): 2179. CrossRef - Levothyroxine: Conventional and Novel Drug Delivery Formulations

Hanqing Liu, Wei Li, Wen Zhang, Shengrong Sun, Chuang Chen

Endocrine Reviews.2023; 44(3): 393. CrossRef - Re: “Exploring the Genetic Link Between Thyroid Dysfunction and Common Psychiatric Disorders: A Specific Hormonal or a General Autoimmune Comorbidity” by Soheili-Nezhad et al.

Christiaan F. Mooij, A.S. Paul van Trotsenburg

Thyroid®.2023; 33(8): 999. CrossRef - Circulating thyroid hormones and clinical parameters of heart failure in men

Iva Turić, Ivan Velat, Željko Bušić, Viktor Čulić

Scientific Reports.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Evaluation of cortical and trabecular bone structure of the mandible in patients using L-Thyroxine

Melike Gulec, Melek Tassoker, Mediha Erturk

BMC Oral Health.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - The Impact of Hypothyroidism on Satisfaction with Care and Treatment and Everyday Living: Results from E-Mode Patient Self-Assessment of Thyroid Therapy, a Cross-Sectional, International Online Patient Survey

Petros Perros, Laszlo Hegedüs, Endre Vezekenyi Nagy, Enrico Papini, Harriet Alexandra Hay, Juan Abad-Madroñero, Amy Johanna Tallett, Megan Bilas, Peter Lakwijk, Alan J. Poots

Thyroid.2022;[Epub] CrossRef

KES

KES

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite