Overweight and Obesity are Risk Factors for Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Propensity Score-Matched Case-Control Study

Article information

Abstract

Although obesity is a risk factor for infection, whether it has the same effect on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) need confirming. We conducted a retrospective propensity score matched case-control study to examine the association between obesity and COVID-19. This study included data from the Nationwide COVID-19 Registry and the Biennial Health Checkup database, until May 30, 2020. We identified 2,231 patients with confirmed COVID-19 and 10-fold-matched negative test controls. Overweight (body mass index [BMI] 23 to 24.9 kg/m2; adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1.03 to 1.30) and class 1 obesity (BMI 25 to 29.9 kg/m2; aOR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.42) had significantly increased COVID-19 risk, while classes 2 and 3 obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) showed similar but non-significant trend. Females and those <50 years had more robust association pattern. Overweight and obesity are possible risk factors of COVID-19.

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has resulted in >28 million confirmed cases and 917,000 deaths as of mid-September 2020 [1]. Although previous epidemiological studies reported that obesity was associated with infectious diseases risk [2–4], whether it has the same effect on COVID-19 needs confirming.

We conducted a retrospective propensity score (PS) matched case-control study, to examine association between obesity and COVID-19 risk using data from the Nationwide Registry of COVID-19 cases and the Biennial Health Checkup database of South Korea.

METHODS

Statement of ethics

This research was conducted in accordance with the ethics requirements of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Institutional Review Board of the Gachon University College of Medicine, Incheon, Republic of Korea (GFIRB2020-118), and written informed consent requirement was waived, since human subjects were not involved in the study.

Data sources

Data were obtained from the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) Nationwide COVID-19 Registry and the Biennial Health Checkup database of the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) of South Korea, until May 30, 2020. The NHIS database was linked to the KCDC COVID-19 registry.

The data regarding comorbidities (identified using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision) were extracted from the NHIS reimbursement database and categorized in Supplemental Table S1. The comorbidities, identified from diagnostic codes, included at least twice according to the reimbursement records covering the past 3 years and dated before COVID-19 onset.

Study patients and definitions

Patients aged ≥20 years who underwent laboratory test for COVID-19 and NHIS health checkup in 2018 and later, were included. COVID-19 diagnosis was made using nasopharyngeal swab or sputum sample, and analyzed using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction to detect SARS-CoV-2 according to the national guidelines [5]. All patients who tested positive were categorized as confirmed cases and the remaining as negative controls. Data on body mass index (BMI) were categorized as normal (BMI <23 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 23.0 to 24.9 kg/m2), class 1 obesity (BMI 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2), and classes 2 and 3 obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) according to the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity guidelines (Supplemental Table S2) [6]. As the primary outcome, association between infection of COVID-19 and BMI categories was analyzed, and association with fasting blood sugar (FBS) was also evaluated.

Statistical analysis

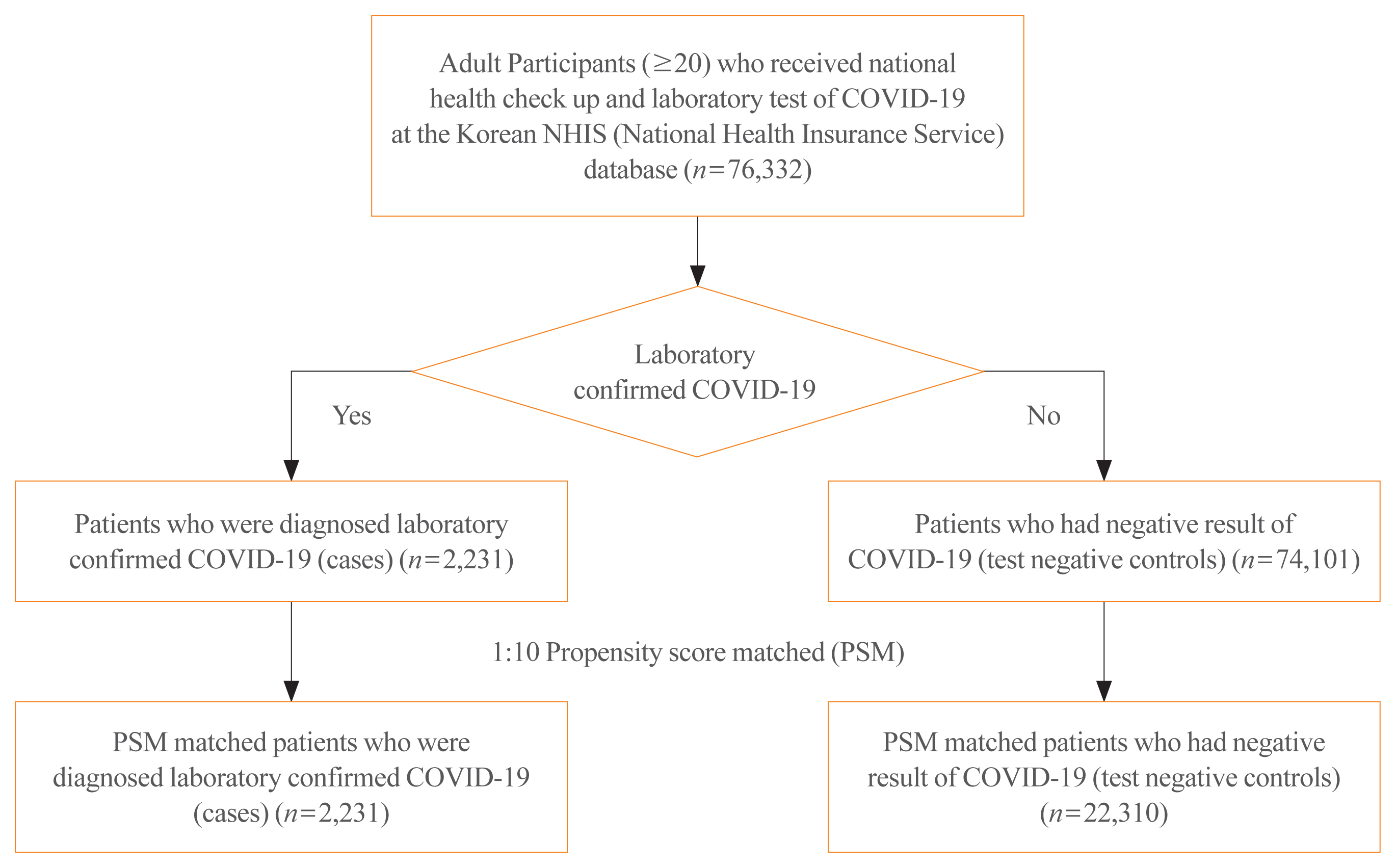

Baseline characteristics of COVID-19 patients and test negative controls were compared using chi-square test and Student’s t test, as appropriate. Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was calculated using standard methods [7] and compared. Adjusted logistic regression models were constructed, based on the following covariates: age, sex, NHIS expanded medical aid coverage, and comorbidities. We constructed PS matched cohorts to mitigate the impact of confounders. PSs for COVID-19 risk were calculated using logistic regressions including the following covariates: age, sex, medical aid coverage, and CCI. Each patient with COVID-19 was matched with up to 10 test negative controls using the greedy neighbor nearest-matching algorithm (Fig. 1). The model was further adjusted in a logistic regression analysis, using age, sex, insurance medical aid coverage, and comorbidities, as covariates. The standardized mean difference in PS matching are presented in Supplemental Table S3. All statistical tests were two-tailed and the threshold for significance was set at P values <0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline demographics between cases and test negative controls

A total of 76,332 individuals aged ≥20 years who underwent a laboratory test for COVID-19 and the NHIS health checkup in 2018 and later, were identified. From the 74,101 negative test controls, 10-fold PS matched controls were selected and analyzed (Fig. 1).

The proportion of females (1,360 of 2,231; 61.0%) and those with medical aid (142 of 2,231; 6.4%) were higher among positive cases than the negative controls. COVID-19 patient group were older than those in the control group. After PS matching, the matched cohort showed similar baseline characteristics except for the proportion with medical aid, diabetes, chronic liver disease, malignancy, and rheumatologic disease (Supplemental Table S4).

Association between BMI category and COVID-19

Overall, higher BMI showed positive association with COVID-19 (Fig. 2). Patients who were overweight (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03 to 1.30; P= 0.015) and had class 1 obesity (aOR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.42; P<0.001) had significantly increased risk of COVID-19 compared to those with normal BMI reading, while patients with classes 2 and 3 obesity showed similar but not significant trend (aOR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.95 to 1.46; P=0.128). The effect of BMI on the risk of COVID-19 was more prominent among women than among men. By age group, the association patterns of overweight and class 1 obesity were robust for all age groups. Classes 2 and 3 obesity showed a significant association in <50 years age group (aOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.15 to 2.13; P=0.004).

Association between fasting blood glucose category and COVID-19

FBS ≥126 mg/dL was significantly associated with COVID-19 only in females (aOR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.69; P=0.02), while the other groups and overall analysis did not show significant differences (Supplemental Table S5).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found overweight and obesity as possible risk factors of COVID-19, especially in females and in <50 years age group. Our findings are consistent with previous reports, which revealed obesity as a significant risk factor for the occurrence, severity, and mortality of COVID-19 [8–12]. Increased expression levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 by adipocytes, overactive renin-angiotensin system due to higher levels of angiotensin II, endothelial dysfunction, and higher risk of thromboembolism have been proposed as possible mechanisms linking obesity with COVID-19 risk [13–15].

The present study found that class 1 obesity (BMI 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2) was also a significant risk factor for COVID-19. Moreover, higher BMI and FBS ≥126 mg/dL were more significantly associated with COVID-19 in females than in males. Some previous studies reported that there may be gender differences in susceptibility to COVID-19 [16,17], and the present study results also suggest this. Interestingly, classes 2 and 3 obesity were significantly associated with increased COVID-19 risk in <50 years age group, while a similar but not significant trend was shown in the older age groups. A small retrospective study reported obesity as a predictive factor affecting COVID-19 severity in young adults <40 years old [18]. This previous report is supported by findings of our study indicating that obesity may have a greater impact on COVID-19 in younger adults.

This study has a few limitations. First, there is the possibility of selection bias. We used data of patients who underwent health checkups in 2018 or later, and it is possible that these patients were more likely to have undergone health checkups, as they may have had more comorbidities. However, to mitigate this confounding factor, we used a robust design with the PS matched analysis. Moreover, we consider that the results reflected more accurately the current body weight, because we used the most recent heath checkup data. Second, we were unable to evaluate the mechanism of the relationship between obesity and COVID-19. However, this study findings confirmed the association between obesity and COVID-19 and we recommend that detailed mechanisms of the relationship be evaluated by further experimental research.

In conclusion, overweight and obesity are possible risk factors of COVID-19, especially in females and in those aged <50 years. Therefore, weight and obesity approaches are important considerations in COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control.

Supplementary Information

ICD-10 Codes Used for the Identification of Comorbidities

Classification of Blood Pressure, Fasting Plasma Glucose, Body Mass Index, and Lipid Profile

Standardized Mean Differences of Propensity Score Matching and Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Who Received Laboratory Test of COVID-19 after Propensity Score Matching

Adjusted ORs for Patients Who Were Confirmed with COVID-19 and Negative Test Controls (Hypertension and Fasting Blood Sugar)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the healthcare professionals dedicated to the treatment of patients with COVID-19 in Korea; and the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the National Health Insurance Service of Korea for their prompt sharing of invaluable national health insurance claims data.

This study was supported by grants from the Gachon University Gil Medical Center (grant numbers 2019-11) and a grant from the Korea Health Technology Research and Development Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea (grant numbers HI14C1135). The sponsors of the study were not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, and the writing of the report; nor the decision to submit the findings of the study for publication.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception or design: W.J., K.H., I.C.H., D.H.L., J.J. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: W.J., R.L., K.H., I.C.H., D.H.L., J.J. Drafting the work or revising: W.J., D.H.L. Final approval of the manuscript: W.J., R.L., K.H., M.K., I.C.H., M.R., D.H.L., J.J.